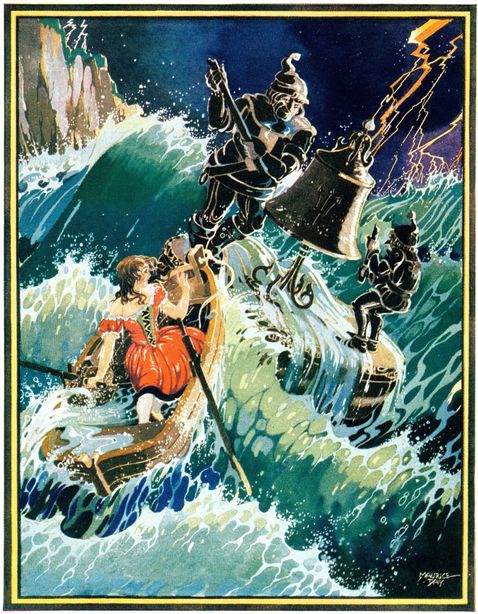

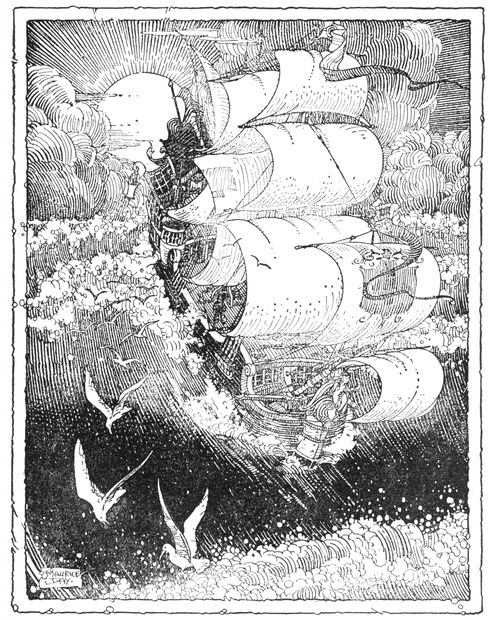

Long and hard fought Thyrza, and presently a great gust of the gale swept her against the Bell of the Sea

The STARLIGHT WONDER BOOK

By HENRY B. BESTON

AUTHOR OF

The FIRELIGHT FAIRY BOOK

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

MAURICE DAY

The ATLANTIC MONTHLY PRESS

BOSTON

COPYRIGHT 1923 BY THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY PRESS, INC.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To

MISS MABEL DAVISON

MY WAR-TIME GODMOTHER

with the

HOMAGE

and

GRATEFUL AFFECTION

of

H·B·B·

| PAGE | |

| THE BELL OF THE EARTH AND THE BELL OF THE SEA | |

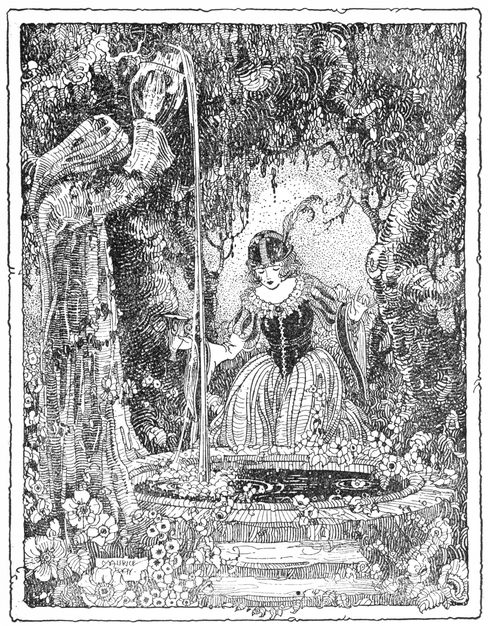

| Long and hard fought Thyrza, and presently a great gust of the gale swept her against the Bell of the Sea | Frontispiece |

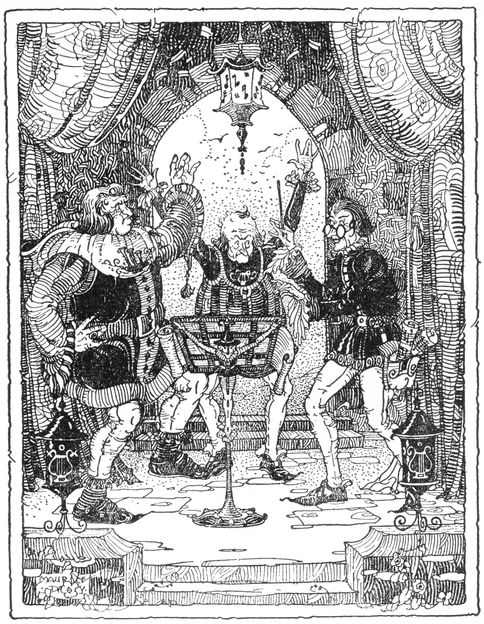

| THE BRAVE GRENADIER | |

| Suddenly the soldier’s foot dislodged a piece of clattering stone, and the hippodrac awoke | 13 |

| THE PALACE OF THE NIGHT | |

| The image in the mirror stood still | 35 |

| THE ENCHANTED BABY | |

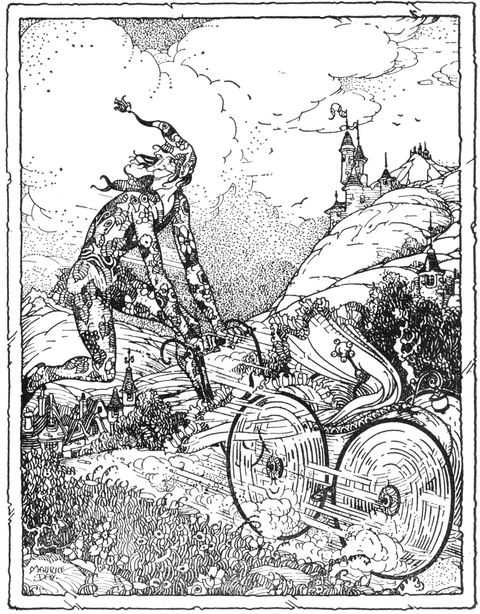

| Over hill, over dale, in a long straight line, fled the Master Thief with the golden perambulator | 57 |

| THE TWO MILLERS | |

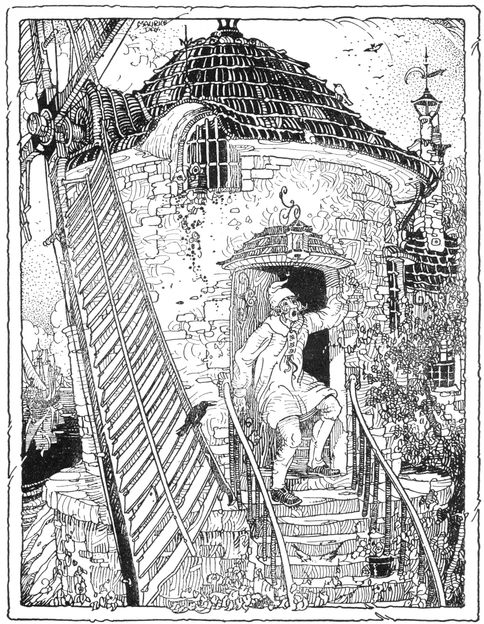

| He lifted a moistened finger to the air. Good heavens, there wasn’t a breath of wind! | 85 |

| THE ADAMANT DOOR | |

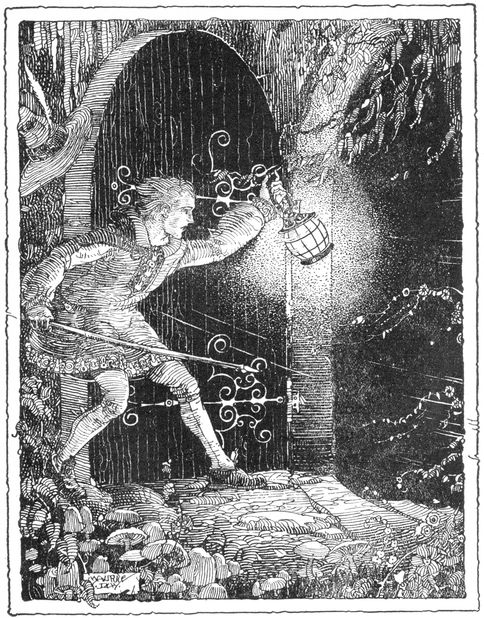

| Summoning up all his courage, Hugh threw open the adamant door | 105 |

| THE CITY OF THE WINTER SLEEP | |

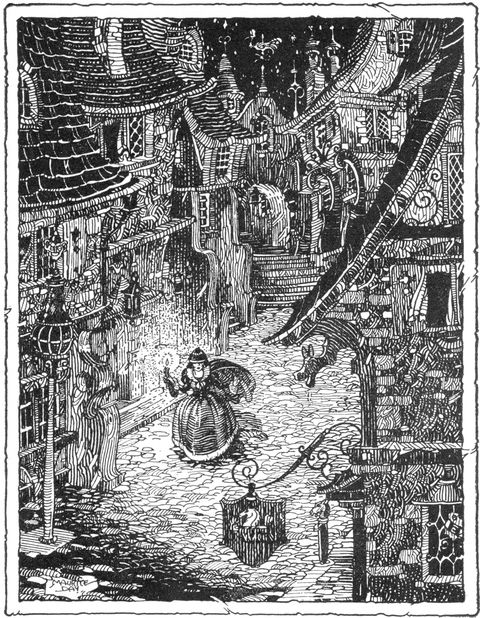

| The runaway Princess stepped forth into the dark street and, taper in hand, hurried to the gate of the city wall | 117 |

| AILEEL AND AILINDA | |

| And now, all at once, there were cries and shouts of alarm. “Run! Run, everybody! The bird! Oh, see the bird!” | 149 |

| THE WONDERFUL TUNE | |

| “No, I do not agree with you,” shouted the Lord Organist | 171 |

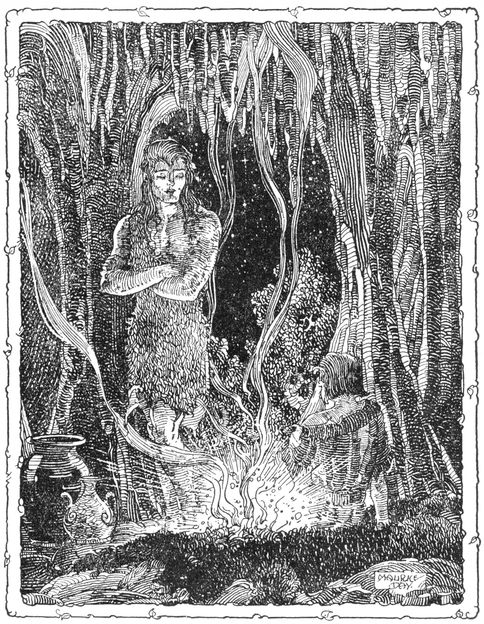

| THE MAN OF THE WILDWOOD | |

| Before him stood the Man of the Wildwood | 187 |

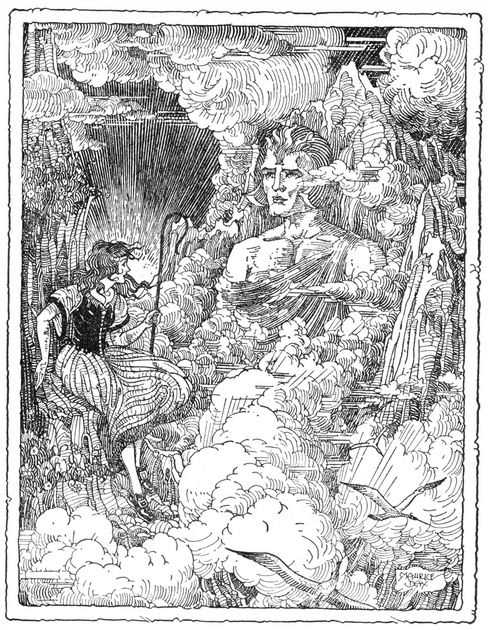

| THE MAIDEN OF THE MOUNTAIN | |

| For a long moment Leoline, awed yet unafraid, gazed at the Giant of the Mountain | 203 |

| THE BELL OF THE EARTH AND THE BELL OF THE SEA | |

| And stowing the Bell of the Earth in the hold of his ship, the young Captain sailed eastward and southward through the sea | 229 |

| THE WOOD BEYOND THE WORLD | |

| Fidelia knelt at the edge of the pool, and filled her golden cup with the waters of memory | 257 |

Once upon a time, during a great battle which was fought through the night in a tempest of lightning and rain, a brave young grenadier came upon one of the enemy lying sorely wounded on the field. Taking pity upon his foeman, the soldier bound up his wounds and carried him from the battle to the shelter of a little wood. Scarce had the wounded youth opened his eyes, when amid a blinding flash of lightning and a peal of tumbling thunder, a green chariot drawn by green dragons rushed downward through the hurrying clouds and sank to earth at the soldier’s side. Bidding the dragons be still, a tall, dark, and stately man wearing a long green mantle descended from the chariot, took the wounded lad in his arms, and thus addressed the grenadier:—

“Generous friend, to you I owe the life of my youngest son. I am the Enchanter of the Green Glen. Take you this little green wand in memory of the great debt I owe you. Whatsoever you strike once with it will continue to grow larger till you cry ‘stop’; whatsoever you strike twice with it will grow smaller till you bid the magic cease. Farewell, brave soldier, and may good fortune walk forever by your side.”

Then, wrapping his wide green mantle about the body of his son, the Wizard bade his scaly, yellow-eyed dragons be on their way, and vanished on high in the tempest and the dark.

And now the wars were over and done, and the soldier found himself mustered out and turned loose to earn his living in the world. Still clad in his grenadier’s uniform, and wearing his blue greatcoat buttoned close about him, he slung his knapsack to his shoulder, fastened it to his belt in front by crossed straps of white leather, put on his big shiny hat, and turned from the camp over the hills and far away.

It was the early autumn of the year: great roaring gusts swept by overhead, singing shrilly through the withered leaves still clinging to the branches, apples lay red ripe in the frost-nipped grass, and the country folk were gleaning in the stubble of the fields. On through the villages went the soldier, hoping to find work for the winter among the farms; he knocked at this door and at that, but ever in vain. Presently the mighty summits of the Adamant Mountains, gleaming with new-fallen snow, rose beyond the bare woods and the lonely fields. Following the great royal road, the soldier tramped on into the very heart of the mountain mass.

“Perhaps I shall meet with better luck in the kingdoms beyond the peaks,” thought the grenadier, as he trudged along. How still it was! Now the soldier could hear the roaring of the river in the gorge below the road, now the cry of the eagles circling high above some desolate crag.

At high noon on the third day, the soldier arrived at the brazen column which marks the descent of the royal road to the kingdoms beyond the hills. A biting wind, keen with the smell of snow, blew from the surrounding peaks, and made the soldier very hungry indeed. Sheltering himself against the giant column, he slipped his knapsack from his shoulder, and looked within for the last of the bread and cheese which a good wife of the mountain villages had given him the day before. Alas, there was but the tiniest crust of bread to be found, and the littlest crumb of cheese! Suddenly, as he fished about in the sack, the grenadier discovered the little green wand. He had quite forgotten it. A notion came into his head to try the magic, and he struck the bit of bread one smart tap.

The moment he did so, the fragment of bread bounced a few inches into the air, and fell back to the ground; soon it was the size of a loaf of bread; a moment or two later the loaf had grown to the size of a table; soon the mass of bread was the size of a small house. And it was growing, growing, growing.

“Stop!” cried the soldier. The magic ceased. The soldier struck the mountain of bread twice.

Again it leaped into the air, but this time it began to grow less. Like to a candle end in the fire, it began to vanish before the soldier’s eyes. Presently it was once more the size of a generous loaf, and thus the soldier bade it remain. Next he enchanted the bit of cheese to an ample size, and found himself provided with victuals fit for a king. Later, when he had eaten his fill, he amused himself by enchanting a pebble into a great rock. And that rock may be seen in the Adamant Mountains to this very day!

At the end of a week’s journey the soldier reached the Golden Plain, which lies between the Adamant Mountains and the sea.

Now at the time of the soldier’s arrival, the people of the Golden Plain were being day by day swept to hunger and ruin by the devastation wrought throughout their land by a hippodrac. Driven by hunger, so some thought, from its stony lair in the forests of the sun, this terrible creature had suddenly swooped down on the harvest fields a month before, and had roamed the land till the precious grain had for the most part been consumed or destroyed. Worse yet, the hippodrac was even then breaking open the royal granaries, in which lay such grain as the citizens had been able to store away.

This terrible creature, I must tell you, was a kind of fearsome winged horse. It was larger than any earthly animal, black as midnight in color, and armored over the chest and head with a sheath of dragon’s scales. Add to this a pair of giant wings, black and lustrous as a raven’s, a wicked horse-like head with huge jaws, hoofs of blue steel, and an appetite like a devouring flame, and you will see that the people of the Golden Plain had true cause for alarm. Black wings outspread, blue hoofs plunging, roaring from the fiery pits of its violet nostrils, the hippodrac was master in the land.

In the hope of ridding themselves of the monster, the people of the Golden Plain offered a huge treasure to whosoever might conquer the invader. In true soldier fashion the grenadier resolved to fight the hippodrac, and win fame and fortune at a blow.

Now the Lord Chancellor of the realm, who ruled the land during the minority of the Princess Mirabel, had no intention whatever of paying the promised reward. Not only had this wicked man stolen so much money from the royal treasury that scarce was a penny left, but also was he miserly, cruel, and avaricious. Torn between fear of the hippodrac and fear of having to empty his own money-bags of the stolen gold in order to pay the reward, the Chancellor wandered back and forth all day through the castle halls. Thus far, however, no one had ever returned to claim the treasure.

After talking with some who had seen the hippodrac, the soldier retired to a little inn to make his plans. Sitting alone in a great settle by the fire, he watched the flames grow ruddier as the afternoon sun sank below the western hills. Presently it was night, a night quiet, cool, and bright with great winter stars.

The grenadier made his way unobserved out of the royal city, and soon arrived in the midst of the ruined and trampled fields. Here the grain had been gathered, bound in sheaves, and left to perish when the harvesters fled; here the uncut stalks had withered in the ground; here stood a house from which everyone had run for his life. Presently the soldier beheld, standing apart on a lonely hill, the crumbling towers of the ruined castle which served as the hippodrac’s den.

A late, wasted, half-moon began to rise. The soldier made his way up the slope, and peered through the doorless portal into the moonlit ruin.

At the end of the great entrance-hall of the castle, its monstrous head resting on the lowest step of the winding stair which led to the roofless banqueting-hall above, lay the monster. The rays of the waning moon, slanting through the broken tracery of a great window, fell on its vast bulk; a rumbling breathing alone disturbed the starry silence of the night.

“I must make my way down those stairs,” said the grenadier to himself, and crept off to seek a way to the banqueting hall above. Finally he managed to find a little stairway in a ruined turret. Creeping along softly, ever so softly, over the floor of the banqueting hall, he reached the head of the great stair and looked down its curving steps to the monster asleep below. Then, step by step by step, the grenadier approached the hippodrac.

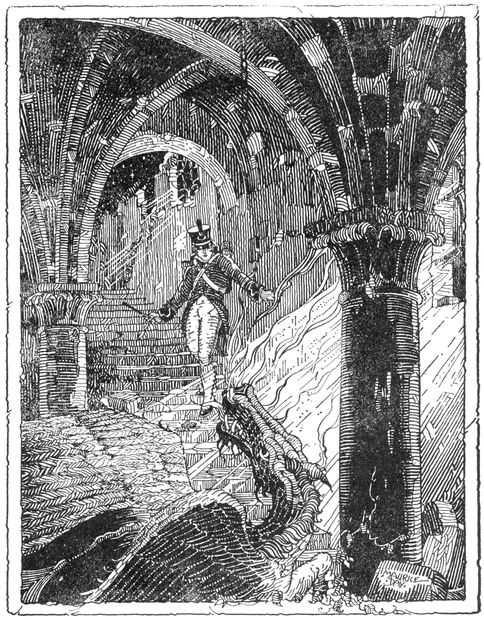

Suddenly the soldier’s foot dislodged a piece of clattering stone. The hippodrac awoke with a scream, but the soldier struck it two swift taps with the little green wand.

The instant he did so, the hippodrac uttered a cry of fright and rage which waked the good folk of the city in their beds, and bounced, wings beating wildly, in the air. The grenadier took refuge at the head of the balustrade. Smaller and smaller grew the furious and bewildered beast. Now it had shrunk to the size of a pony, now it had dwindled to the size of a dog, now it was scarce larger than a kitten.

“Stop!” cried the grenadier. Wild with fright, the tiny monster took wing, and fluttered like a terrified bird into a corner of the ruins. And there, beating about and flapping its wings madly, the grenadier caught it in his high hat, and shook it into his knapsack. This done, he walked swiftly back to the inn, and went to bed.

Now one of the Lord Chancellor’s rascals had been on watch for his return, and when the grenadier returned with the light of victory in his eyes, this spy ran to inform his rogue of a master. Suspecting magic of some kind, the wicked Chancellor made his way to the inn, and stole the green wand while the soldier slept.

Suddenly the soldier’s foot dislodged a piece of clattering stone, and the hippodrac awoke

Early the next morning, the soldier sent word to the counselors of court that he had mastered the hippodrac, and waited their good pleasure to prove the truth of his word. Within a very short time a royal messenger appeared, summoning him before the assembled court at the tenth hour.

And now the soldier, carrying the tiny hippodrac in his knapsack, was led to the judgment hall of the royal palace. The Princess Mirabel sat on the throne of the realm, whilst the Lord Chancellor stood by her side, a smile of triumph on his wicked lips. But the soldier had eyes only for the young Princess, who was as fair as the first wild rose of the year. As for the Princess, it must be confessed that she thought the stalwart young grenadier with the black hair and the blue eyes quite the most pleasant person she had ever seen.

Simply and modestly the grenadier told the story of his capture of the hippodrac. Leaning forward a little, the Princess listened eagerly.

“And your proof of this—?” questioned the Lord Chancellor.

“Is here,” replied the grenadier, and opening his knapsack, he took from it the hippodrac and placed it on the carpet just before the throne. As the soldier had taken the precaution to clip the monster’s wings, the tiny thing could do naught but dance with rage on its little blue hoofs, and lash out madly right and left in a frenzy of fear. A murmur of astonishment rose from the assembly. There was a great craning of necks. All present looked at the Lord Chancellor to hear what he might say.

“That little thing, the great hippodrac?” said the Lord Chancellor, evilly. “Pooh! ’T is a juggler’s kitten, rather. I shall give no reward for this.”

“You dare?” cried the grenadier fiercely. “Wait!” And he reached in his pocket for the little green wand, but, alas, the little green wand was gone.

“Pooh!” said the Chancellor again, watching, with contented eyes, the poor grenadier madly thrusting his hands into every pocket, “You see he cannot do as he pretends. The fellow is an impostor. Ho, guards! Take this rogue and his dancing kitten off to prison.”

“But it looks like the hippodrac,” protested the Princess.

“No! Not a bit of it, not a bit of it!” roared the Chancellor. And he quickly silenced all those who were fain to see justice done, by threatening to send any objector to the royal diamond-mines in the Adamant Mountains.

Left to himself in a lonely cell of the royal prison, the poor grenadier awaited the day of his departure for the mines. Finding the time hang heavy on his hands, he amused himself by trying to tame the tiny hippodrac. To his surprise and pleasure, the fierce little creature made a swift response. Soon it was eating crumbs from his hand. In a fortnight it could spell out words and letters by tapping the floor with its right foreleg! And day by day, its clipped wings grew once more to full size.

“Oh, if you could only get me my green wand again!” said the soldier one morning.

At these words, the hippodrac beat an excited tattoo on the table, and before the soldier could seize it, spread its little gleaming wings, and fled through the barred window out into the world.

All day long the soldier waited its return. “It has flown away forever,” he thought, as twilight fell. A moment later, however, he heard a whir of tiny wings, and the hippodrac returned, the little green wand in its jaws. You may well believe that the soldier was overjoyed! That very night he found means to send a petition to the Princess, asking to be brought before her that he might at last prove the truth of his story.

Now the Chancellor, knowing that his wicked scheme had succeeded, and never dreaming of the possibility of the grenadier’s escape, had gone a-hunting: so the Princess took matters into her own hands, and next morning summoned the grenadier before the court. Alas! Just as the grenadier reached the throne, the Chancellor, hastily summoned by another of his rascally spies, came striding angrily into the judgment hall.

“What means this?” he roared. “How came that fellow to be out of prison? Ho, guards, take him back at once!”

“No!” said the little Princess bravely. “I believe in him, and he shall have justice in my realm!”

“Do you dare defy me?” cried the Chancellor. “Guards, do your duty! I am Regent here.”

A handful of soldiers strode toward the grenadier. With a smile on his lips and in his eyes, the grenadier struck the hippodrac one smart tap with the magic wand.

The creature bounced, and instantly began to increase in size; suddenly it snorted fiercely and reared on its hind legs; once again it screamed even such a scream as it had uttered when the grenadier enchanted it in the ruined castle. People began to fly pell-mell in every direction. Only Mirabel, who was a lass of spirit, stood her ground.

When the hippodrac had reached its full size, the soldier cried “Stop!” Then, for a moment, the monster and the man gazed directly into each other’s eyes. The soldier still smiled.

The hippodrac had understood.

Uttering now the angriest cry of all, the creature darted forward, and seized the Lord Chancellor by the scruff of his ugly neck. Then opening wide its giant wings, it leaped up on all four legs, and flying down the vast hall, crashed through a great window and out into the freedom of the cloudless sky. So terrified was it by its experiences, that it flew back to its lair in the forests of the sun, and never bothered anybody any more.

On the way home, while flying at a great height, it got bored with carrying the Lord Chancellor and let him drop. No one has since heard of this personage. No one ever will.

When the excitement subsided, the citizens hailed the grenadier as the preserver of their country and offered him the treasure which the Chancellor had stolen away. But the grenadier had already found a treasure much more to his liking—the Princess Mirabel. The handsome young couple were married with great pomp and ceremony on New Year’s day.

And thus the brave grenadier became a king, and with Mirabel by his side, ruled over the Golden Plain for many a long and happy year.

Once upon a time there was an Emperor of the Isles, who had but one son, the Prince Porphyrio. On the day which beheld the Prince’s coming of age, the Emperor summoned the youth to his council chamber, and said to him:—

“Dear son, when you were a little child, I pledged to you the hand of the Lady Liria, daughter of my friend and ally, the Emperor of the Plain. You are now of age, and I would fain send you forth to find the Princess and win her for your own.”

Then replied the tall, golden-haired Prince, “Dear father, give me but a brave ship and a gallant crew, and I will this very eve set sail for the Emperor’s city and greet the Lady Liria.”

Pleased with this speech, the Emperor gave orders that a fine ship be swiftly prepared for the voyage. And this was done.

And now it was night, and the vessel lay waiting, her sails gleaming green-white in the moonlight, her ladder shrouds gently swaying against the pale and starry sky. When came the ebb of the midnight tide, the anchors were weighed, the great sails trimmed to the breeze, and the vessel piloted forth to the measureless plain of the sea.

Now it came to pass, as the great ship sped upon her furrowed way, that Porphyrio took it into his head to visit the Fair of the Golden Bear, and fled before the wind to the festival city. Little by little—for the air was but light—the ship left behind her the blue of the deeps, and entered the green waters of the shallows. Suddenly there was a cry of “Land Ho!” and from afar, over the landward hastening waves, Porphyrio beheld the great tower of the Fair. A giant golden image of a bear, standing erect, crowned the high tower-top, and shone dully bright above the haze.

At sundown the Prince, accompanied by his mariners, found himself in the midst of the great Fair, in the very heart of the din, the medley of outlandish costumes, the babel of strange tongues, and the shrill cries of the shopmen and the merchants. Surely there was never such a market place as the Fair of the Golden Bear!

Everything in the world was there to be bought and sold. At one booth a venerable man in a scholar’s gown and velvet cap sold words—rare words, rich words, strange words, beautiful words, and drove a brisk trade with a crowd of poets and lovers; at another an old woman in green sold rosy glasses to those who were at outs with the world; and at still another a joyous fellow in blue offered sunbeams, which he had caught in a mirror and imprisoned in bits of magic glass.

Porphyrio was quite delighted with the sunbeams, which shone night and day, like diamonds aflame with golden fires. “The Lady Liria will surely be pleased with one of these,” thought he, and purchased the finest of all.

Now it came to pass that, as he walked about the Fair with his retinue of sailor-men, Porphyrio caught sight of a rustic fellow in brown corduroys who was carrying a sea bird in a wicker cage. And because he loved the wild folk of the sea, the Prince said to the countryman:—

“Good friend, whither go you with your bird?”

“To the animal merchants, sir,” replied the fellow. “’Tis a wild bird which I found in my field on a morning after a storm. Only look, sir; it wears a circle of feathers on its head, for all the world like a crown.”

“Why, so it does!” said the young Prince. “Come, will you sell him to me?”

“Oh yes, indeed, sir,” replied the countryman. “’Tis yours for a florin of gold and a penny of silver.” And he held out his hand for the sum.

“Good!” said Porphyrio, and he paid the money. Then, to the countryman’s amazement, he threw open the door of the cage, and allowed the sea bird to escape. With a glad cry, and a mighty beating of its gray wings, the creature climbed into a splendor of the sunset, dwindled to a black speck, and vanished from their eyes.

Once more the Prince set sail. For a few days the weather remained tranquil and fair. Then came a night of cloud, and a rushing wind, which increased during the day to a hurricane. Now arose a great din, the howling of the wind through the shrouds, the cracking and straining of the timbers of the ship, the cries of the sailors, and the roaring and foaming of the deep. All night long, through the wild ocean dark, the Prince’s ship drifted nearer and nearer the unknown waters of the Southern Sea. Suddenly, just before the dawn, a tremendous noise was heard; the vessel trembled throughout her length, and crashing down once more on a hidden reef, broke apart. A huge wave swept Porphyrio from the deck, some wreckage hurled itself upon him, and he knew no more.

When he woke again, close upon noon, he found that the waves had carried him to the stony beach of a dark and unknown isle. A stately wall of cliffs of the strangest dark-blue stone girdled it about; to the left, to the right, the rampart swept, solemn, unscalable, and huge. One broken mast of the Prince’s ship still rose forlorn above the tumbling waters on the reefs; but of the gallant crew there was never a sign. With a heavy heart Porphyrio trudged off to look for shelter and for aid. Long hours followed he the curving shore, even till the sun, which had been shining in his face, little by little crept to the side and shone behind, yet never a way to the headland’s height stood forth in the sheer and sombre wall.

And now, of a sudden, and by great good fortune,—for the tide was rising,—Porphyrio, turning the base of an advancing crag, found himself close by a noble promontory that sloped from the cliff-top to foundations in the sea. Half climbing, half dragging himself along the stones and terraces of this ridge, the Prince attained at last the height of the blue wall.

A great dark isle lay open before him—a solitary isle of shadowy lands, gloomy woods, and rocks and hillocks of the same dark stone he had marked before. Save for the faint murmur of the encircling sea below and the sighing of the wind, the isle was as silent as a land beneath the deep: indeed, so still and dark it was, that it seemed as if the night reigned there, forever untroubled by the day. In the very heart of the gloom, its mighty walls and blue battlements lifted high against cloud mountains gathered in the west, a stately palace rose.

After a long, winding journey through a wood dark as a leafy cave, Porphyrio arrived at the portals of the dwelling.

The palace was as silent as a stone. Of silver were its massy doors, and they were sealed and barred, and from turret to foundation stone its windows were with silver shutters closed against the day. Not a sign or a memory of living things was there to be seen.

Wondering in his heart at the mystery, Porphyrio presently made his way into a noble garden, wherein were pools and basins of blue water rimmed about with silver, and tall, dark trees stately as night. Again to his wonderment, the Prince beheld that the flowers in the garden were such as opened only in the night—the pale, fragrant jasmine hid there, the moonflower dreamed, and the shy star-daisy gathered her petals before her face.

Suddenly the Prince heard steps behind him, and turning swiftly, beheld a fair Princess gazing at him with eyes in which wonder, alarm, and hope might all be seen.

“Speak! Who are you? What do you here?” said the Princess quickly.

To this Porphyrio replied that he was a prince who had been shipwrecked on a voyage. And he told the Princess of his adventures.

“Alas,” replied the lady, “You have come to the dark land! Know you not into whose power you have fallen? This dark isle is the dwelling of the Magician of the Night, who rules the fairy world from sunset to the morn. When comes the dawn, his mighty power wanes, and he and his people of the night hasten to this locked and shuttered palace, here to lie hidden from the sunlight which is their enemy and deadly fear. I alone go forth, for I, alas, am a mortal. But hearken to my story.

“I am the Princess Liria (Porphyrio started). My father is the Emperor of the Plain. On midsummer eve, as I was walking with my handmaidens in the garden, a messenger from my father arrived bidding me come at once to the great hall of state. I obeyed the message, and going to the hall, found there the Magician of the Night, who had just presented a haughty petition for my hand. Because of his fear of the Magician, my father was very ill at ease. All looked to me for an answer. I replied courteously that, though I felt highly honored at the demand, I nevertheless felt bound to refuse, for I had been affianced since childhood to another. For you must know, good Prince, that my father was long the true friend and ally of the Emperor of the Isles, and had pledged my hand to his only son, the Prince Porphyrio.

“Would that this were all I had to tell! But—woe to me!—scarce had the Magician, with a mocking smile, bowed low and disappeared into the night, when a terrible storm of his contriving descended upon our unfortunate city, overturning our tallest towers and strewing ruin far and wide. Our torches quenched by the rain and wind, my maidens and I took refuge in a great chamber of the north turret. At the height of the storm the wind suddenly burst open the double portals, there came a great flash of lightning and a roar of thunder, and I beheld the Magician standing tall and motionless between the doors, surrounded by a dozen of his creatures of the night. I cried out, but his servants seized me and led me forth; great wings bore me upward through the very torment of the heavens, a darkness fell on me, and I knew no more. When I awoke, I found myself here in the Palace of the Night.

“Farewell, dear land of the Golden Plain, whose harvests I shall never more see! Farewell, dear Prince Porphyrio of the Isles!”

“But I am Porphyrio!” cried the Prince, “and I was on my way to find you, noble Liria, when the storm swept me to this isle.”

You may be sure the heart of the Princess leaped when she heard these tidings!

Forgetting that he was himself but a shipwrecked wanderer much in need of aid, the Prince, like the brave fellow that he was, could think of nothing but of rescuing his lady from the dark magician; as for the Princess, she could think of naught but the plight of Porphyrio, tossed friendless and forlorn upon the isle. But at length she shook her head and smiled.

“To-day,” said she, “is mine, and to-morrow also; but the Magician has bidden me be prepared for the wedding feast by sundown on the following day. But, look, the shield of the sun breaks the storm clouds close above the waters; twilight approaches; the hour of the magician is at hand; you must go. Hide yourself well to-night, and come to the garden to-morrow when the chimes ring thrice. On yon dark wall you will find some strangely shaped fruits growing; fear not to eat of them when you hunger. Liria the Unhappy bids you farewell, Prince Porphyrio.”

“Farewell, Princess,” replied Porphyrio. “Do not despair. We shall yet outwit the dark Magician!”

And now the Prince lay hid in the heart of a great tree, watching the doors and windows of the palace slowly opening in the twilight. Suddenly huge bells swung forth in waves of heavy sound, strange music played, and the thousand windows filled with the magic glow of moon-fire. All night long the people of the night held festival; but at the break of dawn the silver windows closed slowly on their hinges, the music grew faint, and the murmur died away.

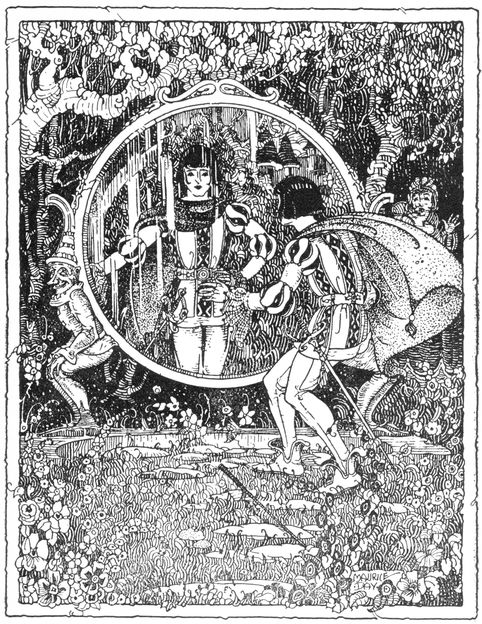

On the second afternoon the Prince, in his impatience, came early to the shadowy garden. The Princess Liria was not to be found, so Porphyrio wandered away into the dark alleys by the pools. Suddenly he found himself looking at his own reflection in a huge round mirror which two marble statues supported between them, one at each side. Happening to move a little, the Prince discovered that his reflection did not move! He lifted an arm, the image remained motionless; he shook his head, the mirror gave no sign. Puzzled, Porphyrio left the spot, and saw his reflection remaining behind the glass.

Presently he heard the welcome footsteps of Liria. And as the lovers walked and talked and discussed plans of escape, the Prince chanced to tell of the mirror he had found. Uttering a little gasp of alarm, the Princess cried: “Now we are lost indeed! Yon mirror is a mirror of memory, and reveals to the Magician the faces of those who walk these paths. As soon as he sees your reflection therein,—and he gazes into the glass every eve,—his demons will be sent in search of you. There is one hope and one only.

“Go you once more to the sea; follow the cliff for a league to the west of the promontory, and you will find at its base the opening of an ocean cave. When you arrive there the tide will be at half-flood, and the entrance will still be visible above the waves. Fight your way within and climb to the cavern’s height. Little by little the rising tide will seal the portal and hide you from the search. Make haste, dear Porphyrio, for there is not an instant to lose! Oh, that I had warned you!”

The image in the mirror stood still

Ragingly angry with himself for being a meddlesome fool, Porphyrio hurried down to the sea and sought out the cave. Twilight was at hand; the tide was rising fast, already the entrance was almost closed by the sea. Buffeted by the breakers and tossed against the cliff as he strode, the Prince at length made his way into the cave and climbed to a shelf of rock above the height of the tide. A few minutes later, the water closed the entrance completely, thus imprisoning Porphyrio in a hollow darkness through which the ebb and flow of the outer sea swept with chuckles and whispering laughter. All night long waited Porphyrio in the cold, watery dark.

Toward the end of the Prince’s vigil, the earth suddenly shook, the waters hushed, and through the silence and the dark Porphyrio heard the long thunder of a mighty overthrow.

“What can that be?” thought he.

When the first red rays of the sun streamed along the rocky floor of the cave, Porphyrio descended from his refuge, and walked out of the cave-mouth to the sea.

Now, as Porphyrio walked along the shore, it came to pass that he discerned, deeply embedded in the bluish sands and lashed about with ropes of matted weed, the splendid painted chest which had lain in his cabin on the ship. Its brazen lock, though tarnished by the waters, was still highly clasped; but sea and stone had broken the wood loose from the hasps, and the Prince had little difficulty in raising the lid. With a rueful smile he gazed down into his robes and fine array lying musty and sand-strewn within. There lay his prince’s circlet of gold, here his jeweled sword of state, here the rich gifts he had meant for the Princess Liria. And among these, tucked away in the very corner of the chest, Porphyrio found the sunbeam he had purchased at the Fair of the Golden Bear.

“Were Liria armed with this,” cried he, “the Magician of the Night could not prevail against her!” At the thought, a new strength leaped in his weary heart, and he hurried along the cliff toward the promontory. The storm had now cleared away, the ocean thundered and broke into silvery white foam at the foot of the blue ramparts, and the Isle of the Night raised itself defiantly against a bright and royal sun.

The Magician, however, had not been idle. The mirror had told its story; a search had been made; a legion of creatures had sought Porphyrio in every corner of the isle. Compelled by the approach of dawn to abandon this pursuit, the Magician resolved to render the island unapproachable from the sea. With a spell of tremendous power he caused the promontory to break from the other cliff and fall in scattered and monstrous ruin to the beach below. It was the thunder of this overthrow which had shaken the earth and sounded through the cave.

As a last precaution, the Magician forbade Liria to leave the Palace of the Night, and locked and sealed the doors and windows, every one.

Presently the Prince, hastening along the beach, came in sight of the ruined headland, and a great fear laid its icy hand on his heart as he beheld the triumph of his enemy. How was he to reach the headland height? The cliff-wall now circled the entire island without a break. League after league he trudged, along the shore, through the tide, searching, searching for some way to scale the overhanging walls. Higher and higher climbed the sun. The shadows fell to the east, the afternoon waned, and still Porphyrio had found no path to the top. Desperate at last, he attempted to scale the steep face of the blue precipice. From ledge to ledge, climbing with torn fingers and aching arms, struggled the Prince, and presently, his further advance barred, fell backward, faint and overcome, on a shelf of rock high above the sea.

When his strength returned, he found himself close by an eyrie of sea birds brooding on their nests in shelves and rifts of the rock. With a great clamor of piping and crying the creatures rose startled from their nests, so filling the air with wings that Porphyrio closed his eyes. Suddenly the master of the eyrie, uttering a joyous call, swept down close to the Prince, and with an upward surge of his heart Porphyrio recognized the winged king whose freedom he had purchased at the Fair of the Golden Bear! And now the sea birds gathered about the Prince, some gathering folds of his garments into their talons, others lifting him on broad wings, till presently he was borne from the narrow ledge and the sound of the sea into the splendor and silence of the sky.

The end of day was at hand. Unveiled of any wisp of cloud, the fiery sun lay just above the western waters, its lower rim almost resting on the waves. Once again approached the hour of the Magician of the Night.

The cloud of sea birds flew inland over the blue isle, and settled to earth at the very doors of the Palace of the Night. And opening his arms to them, Porphyrio cried aloud his thanks as they wheeled and fled.

The Prince walked boldly to the great door, and blew a loud blast on the warder’s horn. There came no answer to his call. The Palace of the Night remained silent and dark. The sun’s rim dipped; a little breeze made its way from the sea through the mysterious gardens; the flowers of the night stirred like sleepers in a dream.

“O jewel of the sun,” cried Porphyrio, “Give me now your aid!” And with these words he touched the sunbeam to the lock. A crack resounded, then a shattering crash, and the doors swung open wide. Hastening on twixt other and other doors and through heavy tapestries, Porphyrio at length found himself at the thresh-hold of the great hall of the Palace of the Night. Rich hangings of dark blue velvet, strewn with stars of silver and gold, hung from the giant walls; a thousand lamps of pale moon-fire swayed on silver chains from the unseen height o’erhead; there were huge columns, and dark aisles. To one side of the hall, by a silver throne raised upon a dais, stood the Magician of the Night, his arms folded on his breast. Proud and pale by his side, near a second throne, stood the Princess Liria. About them were gathered the people of the Night.

As the doors parted, all turned to gaze at Porphyrio.

Fixing his dark eyes upon the Prince, the Magician spake a terrible incantation; but his words shattered themselves against the sunbeam as a threatening wave breaks to drift and foam against a crag.

“Seize him!” commanded the Magician.

At these words a host of dark beings surged about Porphyrio, encircling him, yet afraid to attack. Porphyrio took Liria by the hand, and led her toward the door. But even as he did so, the Magician caused awesome silvery fires to bar the outward way.

At the horizon’s edge, the waters were leaping up about the sun.

Baffled by the flame, Porphyrio, still guarding Liria, fought his way toward a great stair at the very end of the hall. In the wall there, barred with silver and shuttered with stone, a giant circular window faced the west. And now there rose a tumult through the hall, and sounds of magic and thunder. Nothing daunted, Porphyrio touched the sunbeam to the window-bar, and threw the double shutters open wide. The sun was yet above the wave, sky and water were aflame, and the great tide of sunlight swept into the Palace of the Night like the music of many trumpets.

From all within the Palace a great wailing cry arose that presently died away. When Porphyrio and Liria turned to gaze, the Magician and his people had vanished, conquered and forever powerless. And the velvet hangings were but cobwebs clinging to the walls, and the lamps of moon-fire but empty shells.

Then Porphyrio and Liria walked hand in hand to the darkening sea, and beheld there a brave merchant-ship which the sea bird was guiding to the isle. You may be sure it did not take the jolly mariners long to rescue the lovers from the headland! And thus the Prince and Princess fared to Liria’s realm, where there their marriage was celebrated with the greatest ceremony.

In time Porphyrio became a king and Liria a queen, and thus they lived happily ever after.

Once upon a time the King of a great country had a quarrel with a goblin. Now it chanced that the King had the best of the dispute, and this so angered the goblin that he departed from the realm and cast about for an opportunity to do a mischief to his foe.

Now, as the goblin bided his time, it came to pass that the King and the Queen, who had long been childless, became the proud parents of a bouncing baby boy. From rosy summer morn to the murmuring quiet of a summer night, the whole realm gave itself over to rejoicing. Bells rang from the towers in cities and steeples in the fields, cannon boomed from castle towers, and small cakes, each one iced with the Prince’s monogram in red and white sugar, were distributed by royal command among the children of the realm.

Now it was the custom of the country that the heir to the throne be shown to the assembled nobility of the realm on the first day of his seventh week in this changing world of ours, and presently this day stood at hand upon the calendar.

On the afternoon of the ceremony, the scene within the great hall of the palace was magnificence itself! Assembled by thousands and ten thousands, the magnificoes of the land, all in ceremonial attire, moved or tried to move about; but as the huge hall was crowded to its bulging doors, this was difficult, and there were, I regret to say, the usual faintings from lack of air, cries of protest, bad-tempered pushing, caps knocked awry, crumpled ruffs, and lost jewels.

Suddenly the great bell of the palace set up a ponderous and solemn booming—the ceremony was about to begin! Mercilessly crowding back the already densely jammed magnificoes on the toes of still other magnificoes, a number of gentleman ushers contrived to open an aisle the length of the hall, and when this feat had been accomplished, the two tallest sergeants in the royal army opened the double portals leading forth from the royal drawing-room. And now, heralded by a great ringing peal of golden trumpets, and accompanied by a crash of exultant thunder on the palace organ, a noble procession slowly advanced through the gateway into the hall. The generalissimo of the royal armies came first, marching solemnly and quite alone, for he was marshal of the occasion; then came trumpeters in green and yellow; then a chosen detail of giant grenadiers dressed in rose-red and silver-grey; then pages scattering flowers from golden baskets; then a little space; and then, advancing with the dignity of a cloud; appeared the Lord Chancellor, wheeling in the baby.

Of finest yellow gold were the wheels and push-bar of the perambulator, whilst the carriage part had been hollowed from a single stupendous opal! Amid a deafening din of huzzas and shouts and bell clangs, the procession solemnly advanced to a dais raised at the head of the hall.

Suddenly an invisible shape fluttered in through a window, muttered something beside the baby’s cradle, uttered a mocking goblin laugh, and fled away unperceived and unsuspected.

After wheeling the baby to the centre of the dais, the Lord Chancellor gave a signal to the trumpeters to break into the national anthem, and bent over the cradle to take the infant and show him to the throng. To his horror, the cradle was empty! The little Prince’s pillow was there, the coverlet edged with turquoise, and the rattle filled with seed pearls—but no baby.

“The baby! The baby! Where’s the baby?” gulped the Lord Chancellor, scarce able to speak. An awkward pause followed: excited whispers, conjectures, rumors buzzed through the audience. Presently, as the truth began to spread, a growing uproar rocked the hall. Soon everybody was busily looking here and there—lifting up edges of carpets, poking about behind curtains, staring at the ceiling, and examining corners.

All at once a baby’s cry was heard, faint to be sure, but quite unmistakable.

“Search, search, my friends!” cried the King. “The Grand Cross of the Order of the Bluebird to whosoever discovers my child!”

The baby’s cry was heard again! Where could he be?

Suddenly a clever young lady-in-waiting, who had been searching the opal carriage, uttered a piercing shriek. While groping about in the perambulator, she had felt the baby, but had been unable to see him. Like a sudden crumbling of walls, the dreadful truth broke upon everyone present.

The baby had become invisible!

Invisible he was, and invisible he remained. You may well believe that his upbringing was indeed a difficult task! To make matters worse, it was soon discovered that not only was the Prince himself totally invisible, but also that such clothes as touched him became invisible, too. One could feel the little Prince, one could hear him—and that was all. Thus, if he crept away on the nursery floor, one had either to grope for him through the clear air, carefully feeling here and feeling there, or wait until he cried. No wonder the poor Queen was forever searching the land for new nurses-in-waiting, and forever sending home nurses whose nerves had proved unequal to the strain! One could never tell what might be happening.

On one occasion, for instance, the child actually managed to escape from his nursery to the sweeping lawns of the royal palace, and the entire national army, working in scout formation, had to spend the whole afternoon creeping about on its hands and knees before the prince was found asleep in the shelter of a plum tree.

Now, when every attempt to undo the spell had failed, it came to pass that the King went to visit the Wise Man of Pansophia, a learned sage who sat in a wing chair beneath a green striped umbrella at the crossroads of the world, giving counsel to all comers. This sage was clad in the stately folds of a full black gown, a round black velvet cap rested on the crown of his snow-white head, a broad white beard lay spread upon his breast, and on his nose were huge round spectacles, over whose edge he looked with an air of solemn authority.

Beginning at the umbrella, an army of questioners, patiently waiting in single file, stretched dozens of miles across the rolling land and disappeared, still unbroken, over the crest of a distant hill. These patient folk, it is a pleasure to relate, courteously gave way to the unhappy King.

When he had heard the King’s story, the Wise Man shook his venerable head, and replied in a voice which sounded like the booming of waves on a resounding shore:—

“The spell which binds your son is a mighty one, and can only be removed by touching him with the spell-dispeller, the all-powerful talisman given your ancestor, King Decimo, by his fairy bride.”

“Alas,” replied the King, “the spell-dispeller was stolen from the royal treasury twenty years ago. Could you not tell us who stole it, or where it may be found?”

“Was it not the only spell-dispeller in the whole wide world?” questioned the Wise Man.

“It was,” replied the King with a sad, assenting nod.

“Then it was stolen from you by the Master Thief of the Adamant Mountains,” boomed the Wise Man.

“And perhaps you can tell us where he can be found,” said the King. The Wise Man shook his head.

“Ask me where lies the raindrop which fell yesterday in the river,” replied the Wise Man, “but ask me not where dwells the Master Thief. I do not know. No one knows. But as for breaking the spell, it is the spell-dispeller or nothing. Would that I could help you more!”

And, bidding the King a ceremonious farewell, the sage turned his attention to the questioner at the head of the long line, a stout peasant-fellow whose cottage chimney failed to draw.

But now you must hear of the Master Thief of the Adamant Mountains.

This mysterious personage, of whom all had heard, but whom none had seen, dwelt in a secret house in a lost valley of the mountains, a house so artfully shaped and so cunningly concealed with vines and branches, that the very birds of the air were deceived by it and would often come to roost on the chimney, mistaking it for a chestnut tree! As for the Master Thief himself, a kind of living bean-pole was he, for he was taller than the tallest, leaner than the leanest, and provided with a pair of long, tireless legs which could outrun and outlast the swiftest coursers in the land.

During the night, he moved through the world in a strange garment of pitchy blue-black, fitted as close to him as the skin to an eel; during the day, he wore a marvelous vesture on which were painted leaves, spots of sun, dabs of blue shade, and stripes of earthy brown.

Now this Master Thief was no ordinary robber, for he stole not for stealing’s sake, but only to gather new rarities for a wonderful museum he housed in the caverns under his dwelling. Surely there was never such a marvelous museum as the museum of the Master Thief!

Deep in the solemn echoing caves, ticketed and labeled each one, and arranged in order, shelf on shelf, was to be found the finest specimen of everything in the world which men had made or loved. The most comfortable chair in the world was there, the pointedest pin, the warmest blanket, the loudest drum, the stickiest glue, the most interesting book, the funniest joke, the largest diamond, the most lifelike stuffed cat, the handsomest lamp-shade, and a thousand things more. To relabel his collection, to move it about, to do things to it and with it was the supreme delight of the Master Thief. Seated in the most comfortable chair in the world, finger tips together, he spent hours gloating on his treasures, and wondering if he lacked aught beneath the sun. Presently he chanced to hear of the invisible baby’s opal perambulator, and instantly determined to add this new wonder to his gallery.

Going first to his secret den, he spun for himself a globe of delicate glass, spoke five words into it, and sealed them snug within. Next, he attired himself in his parti-colored suit, put the globe in his pocket, and fled on his long legs over hill and over dale to the royal city.

Arriving late in the afternoon, he made his way without difficulty into the gardens of the palace. The day was fair as only a day on the threshold of summer may be, and the opal perambulator stood unattended in the shade of a clump of ancient trees. Magnificently clad, a number of royal nurses were standing about the silver fence which enclosed the prince’s romping-yard. Far off, in the sunny distance, sounded the drums and fifes of the palace soldiery.

And now, creeping nearer unobserved, the Master Thief took the crystal globe from his pocket and tossed it near the group. Striking the ground, the globe burst with the faintest crystal tinkle, and the words that the cunning Master Thief had sealed within escaped into the air. And these words were:—

Oh, look at the balloon!

Immediately all the nurses looked to the sky to see the imaginary balloon, and while they were looking here and looking there, the Master Thief sprang to the opal perambulator, released the brake on the golden wheels, and, pushing the carriage ahead of him, ran like mad down the flower-bordered alleyways and out the garden gates to the highroad.

Over hill, over dale, in a long straight line, fled the Master Thief with the golden perambulator

Across the landscape in a long straight line fled the Master Thief on his wonderful legs, pushing the perambulator all the while. Now they saw him bouncing it across furrowed fields, now they saw it speed like a jeweled boat through a sea of waving green grain, now they beheld it scattering the silly sheep in the upland wilds.

Presently the bells of the city set up the maddest ringing; foot soldiers were turned out on the roads, and squadrons of cavalry were sent galloping after; but all in vain—the jeweled carriage, blazing in the western glow, sped like a meteor over the land. The last they saw of it was a moving streak of light along the steep slope of a mountain, a light which gleamed for a moment on the crest like a large, misplaced, and iridescent star, and then swiftly sank from view.

When the Master Thief reached his secret haven in the valley, he shouted aloud for triumph, and swiftly wheeled the perambulator down to the museum. The most magnificent perambulator in the world! Once more drawing forth the most comfortable chair, the Master Thief sank into it and contemplated his newest prize.

Suddenly, a strange sound, half cry, half gurgle caused him to sit bolt upright. Had someone discovered his secret treasury? What could it mean? And now there came a second cry which ended in a long protesting wail.

The Master Thief had stolen the invisible baby along with the carriage!

Now the notion of having to take care of a baby, of any baby, was a matter which might well alarm the Master Thief; but as for an invisible baby, that was indeed a trial! All at once, however, the Master Thief slapped his knee and chuckled for joy—he had thought of the spell-dispeller! Holding aloft the brightest lantern in the world, the robber made his way to the little side-cavern in which he had placed the talisman.

His heart jumped. The spell-dispeller was gone!

Baffled and perplexed, the Master Thief began a nervous search of the little cavern; but never a sign of the spell-dispeller could he find. Vowing not to restore the Prince till he had found the talisman and tested its power, the Master Thief at length abandoned the search and carried the Prince through the caverns to his dwelling.

And now days passed, and months passed, and even years, without bringing to light the spell-dispeller. From an invisible infant the Prince grew to be an invisible boy, whose merry voice and friendly presence played about the house of the Master Thief like a capful of summer wind on a mountain lake.

Heigho, but after all it wasn’t so bad to be invisible! One could see things and find things hidden away from all other mortals; one could climb to the side of a bird’s nest, sit still, and watch the mother bird feed her young; one could dive, unseen, into the clear, cold pools of the mountain streams and pinch the lurking trout by their rippling tails; one could follow the squirrel to his secret granary!

Now, during the Prince’s fifteenth year, it came to pass that the Master Thief suddenly became ashamed of his wicked ways, so ashamed indeed that he resolved not only to forgo further collecting but also to return every single thing he had stolen! The invisible Prince, I am glad to tell you, was of the greatest possible service to the Master Thief in this honest task. And now, all over the kingdoms of the world, people began to find their stolen possessions waiting for them when they came down to breakfast in the morning: the stuffed cat became once more the pride of the Blue Tower, the most interesting book went back to its place on the shelves of the royal library, the golden scroll of the funniest joke appeared as if by magic on the wall of the king’s own room. Alas for human waywardness, there were actually people who had grown so accustomed to the loss of their belongings that they reviled the Master Thief for their return. Dreadful to relate,—the style having changed,—the handsomest lamp-shade was actually tossed in a well!

At the end of the fifth year, the opal perambulator and the invisible Prince were the only two stolen things left to return. The invisible youth was twenty years old. With a sorrowful heart, for the youth was as dear to him as a son, the repentant Master Thief began preparations to restore prince and perambulator to the unhappy parents.

Now it came to pass that, on the morning of departure, the Master Thief descended for the last time to the forlorn and dusty corridors of his great museum and walked about the galleries, leaving footprints in the dust and musing on the glories that had been. Here had stood the shiniest rubber-plant, here the most beautiful hat-rack, here the only eraser which had never rubbed a hole in the paper. A tear gathered in his eye. He had loved them; he had stolen them; he had restored them; he was free!

All at once his glance, roving empty shelves, fell on a tiny box wedged in a sombre corner. With a loud shout of joy, the Master Thief recognized the spell-dispeller! It had fallen behind a shelf and had lain there concealed for almost twenty years! Thrusting it into his pocket’s depth, the Master Thief bounded up the secret stairs to the joy of the sun.

After a pleasant rambling journey in a huge coach, the Master Thief and the invisible Prince reached the city at the twilight hour, and took lodgings at a quiet, comfortable inn. The invisible Prince, I must remind you, was still invisible.

Now it came to pass that when supper had been served and eaten, the Master Thief and the invisible Prince went for a stroll through the royal city. Much to the surprise of the travelers, they found the city hung with streamers and bunting of the gayest kind. Stranger still, in spite of this display, the citizens of the royal city appeared to be particularly out of spirits.

“Good host,” said the Master Thief to the landlord of the inn, “pray what means this air of jubilee? Do you make merry for some kingly festival?”

“A festival, yes,” replied the host, looking about to see if anyone were listening, “festival it is, but only in name. Have you not heard the news? Let us walk a little to one side and I will tell you the story.

“Three years ago our gracious sovereign, the good King Valdoro the Fourth—weary of the cares of state and still stricken to the heart by the loss of his son, the invisible Prince of whom you may have heard—gave over the guidance of the kingdom to the Marquis Malicorn. Last week this official made himself master of the royal power, imprisoned our dear King and Queen in a dark tower, and proclaimed himself successor to the throne. The coronation is to be held to-morrow afternoon in the great hall of the royal palace. Alas for the people and the nation! Oh, if the invisible Prince would only return!”

To this the Master Thief nodded his head, his busy brain plotting all the while. All at once he smiled. He had devised a plan.

And now it was once more the great hall of the castle, and once more a sunny afternoon. Bells rang, but their cry was wingless and leaden, and there was a dull and joyless note in the cannon’s roar. Crowded as densely together as ever they were twenty years before, the magnificoes sullenly awaited the arrival of the usurper and his train.

Presently the portals were once more swept apart, revealing Malicorn and his followers. Not a sound rose from the assembly.

Growling for rage beneath a huge pair of dragoon’s whiskers, the wicked Marquis made his way to the dais and the coronation chair. The noise of bells and cannon ceased. An official in blue advanced with the royal robe.

Just as he was about to throw it over the waiting shoulders of the usurper, an invisible something snatched the robe from him and, lo, it melted into the air!

Exceedingly angry, yet disturbed at heart, Malicorn hoped for better luck with the sceptre, but this, too, was snatched by an invisible hand. As for the royal crown, it vanished from its purple cushion in the twinkling of an eye.

Speechless with rage, Malicorn now rose to his feet, and stood before the throne, glaring about into the air. Cries of defiance, mingled with shouts of derision, rose from among the magnificoes. And now, even as the turmoil was at its height, the Master Thief, who had been concealed behind some curtains, strode boldly forth to the dais, thrust Malicorn aside with a sweep of his long arms, and shouted to the audience:—

“Magnificoes of the Realm, you came to see your King. Your rightful King is here. Would you behold him?”

“Yes!” shouted the assembly in one voice. And now the Master Thief touched the invisible Prince with the spell-dispeller.

The instant he did so a flash of deep golden light set everyone blinking, fairy music was heard, and suddenly the invisible Prince stood visible before the throne. He was tall, dark-haired, brown-eyed, and a bit slim, and the crown was on his head, the robe on his shoulders, and the sceptre in his hand.

And now the bells and cannon began to boom in real earnest, and a gay breeze came sweeping in to toss the flags and banners that had hung so still. Overcome by emotion, the generalissimo seized the Lord Chancellor by the waist and swung him into a jig, the soldiers all tossed their caps into the air and cheered like mad, whilst the organist became so excited that he began to play two tunes at once. Everybody was laughing and hallooing and hurrahing.

As for Malicorn and his crew, they were tumbling out the back door as fast as their legs could carry them, and nobody has seen them from that day to this.

Presently the old King and the Queen, released from the dark tower, came hurrying in to greet their son.

“He resembles you, my dear,” whispered the King to the Queen.

The Master Thief was forgiven everything.

Singing and rejoicing, the people of the city poured from the houses into the sunny streets.

Clang, clang! Boom! Clang, clang! Boom, boom! Boom! Boom!

And they all lived happily ever after.

Once upon a time, in a pleasant country of meadows sweeping seaward from wooded inland heights, there were two millers and two mills. If you came to the country in a ship, you saw the windmill first, for it was built upon a tongue of land rising above the wide salt meadows and the washing midnight-tides; but if you came to the country by the land, it was the water mill you saw, for it stood beside the highway in the valley of a brooklet rushing to the sea.

Now the wind-miller, who was a great tall man with blue eyes and fair hair, had a daughter named Cecily, whilst the water-miller, who was a little nimble man with a red face and crisp, black curls, had a son named Valentine. And because both the millers were merry men, and there was a plenty of grain for both the mills to grind, these millers were excellent cronies, and the maiden Cecily had been betrothed to the young man Valentine.

Every eve, when the day’s task at the water mill had been brought to an end, the gates lowered, and the brooklet turned free to rush unhindered down the glen, Valentine would walk from his wooded hills to the headland by the sea, and call at the mill for Cecily. The nights were often still, and the golden shield of the moon, rising over the hilly woods, gleamed upon the curling foam of the little long waves, and filled their glassy hollows with her light.

Now it befell that as Valentine and Cecily walked by the shore on such a night, they heard from the hollow of the hills a faint and far-off rumble like the echoing of thunder. Such mysterious sounds were forever rising in the hills, and because no one could tell whence they came, a legend had grown up that somewhere in the forest depths there dwelt a hidden someone, known as the Husbandman of the Hills.

“Listen, Valentine,” said Cecily, “the Husbandman of the Hills is closing the door of his barn. Think you that some day a mortal may find him in his hiding-place in the hills?”

“But suppose it were naught but an idle tale?” said the merry youth, with a smile.

“Oh no, Valentine,” said the maiden seriously. “All my life long have I dwelt here on the shore, and heard the mysterious echoes from the hills. Sometimes the sound is of the lowing of cattle, sometimes of the threshing of grain, sometimes ’tis the creaking of a hay wain in a field. And always the old and wise tell of the Husbandman of the Hills. Some day a mortal will find the hidden Husbandman—do you but wait and see.”

It was the early summer now, and all went merry as a marriage bell. The heavy water-wheel turned with a rolling thunder and a sound of endless splashing; and the four arms of the windmill spun with a windy thrum and a clock-like clack from the rising of the wind to the calm of sundown and the eve.

And now, alas, events were at hand which were to shatter the plans of the two millers and wreck the hopes of Cecily and Valentine!

At the close of the harvest-tide, the Princess Celestia, only daughter of the King and Queen of the country, was going to be married. Now it chanced that the Queen, her mother, was famous in the land as a maker of cake, and presently this good lady promised her daughter a wedding cake so splendid and delicious that painters would beg to be allowed to paint its portrait, and poets to praise it in glorious and immortal song.

Yes, the Queen would make the cake with her own white hands, the batter should be mixed in a golden bowl with a golden spoon, the two best hens in the kingdom should be summoned to lay the eggs, the oven should have a door of diamonds, and as for the flour, that should come from the finest fields and the best mill in all the land.

“I know what I’ll do; I’ll offer a rich reward for the best flour,” said the good Queen. And calling the royal herald to her presence, she bade him summon all good millers to strive for the prize, and to bring of their new flour to the palace at the close of the harvest yield.

Now it chanced that the Queen’s herald, all dressed in blue-and-white and sounding a silver horn, came cantering first to the water-miller’s door.

“I should like to win that treasure,” said the water-miller to himself, musing in the doorway.

“After all, my flour is better than the wind-miller’s meal. That treasure should be mine, must be mine. Yes, mine, mine, mine!”

Now it was the custom of the country for millers to visit the farms in midsummer, view the growing, green grain, and bargain with the husbandmen for the yield of the tossing fields. Suddenly the water-miller, coveting the treasure, determined to purchase all the standing grain, so that the wind-miller should not have any good grain to grind! And this he did, forgetting the while that the deed was sharp and unfriendly.

A day or two passed, and presently the wind-miller climbed to the saddle of his fat white steed, and rode away to buy his customary grain. Alas, there was none to be had. Every turn of the road disclosed new fields of grain, but every single ear was pledged to the miller by the brook!

At first—I must tell you—the wind-miller was more hurt than angry at his old crony’s trickery; but the more he thought of it the angrier he grew. Storming about the windmill in a rage, he gave a great roar for Cecily, and when the frightened maiden appeared before him, he bade her dismiss all thoughts of Valentine from her heart, and consider herself fortunate to be rid of the son of such a father.

The water-miller, however, was not to be outdone. The moment he heard of the wind-miller’s wrath, he too fell into a rage, and presently forbade Valentine, on pain of dismissal, so much as to look at the maiden Cecily.

And now the youth and the maiden were very sad indeed, for in spite of the strife between their fathers, they continued to love each other very much. Presently Valentine could endure it all no more, and stole away one night to have a word with Cecily.

The mill brook was babbling in the dark when Valentine returned to the mill, and a single light was burning in a window by the door. Opening the portal gently, the youth presently discovered his father seated on the stair clad in a flowered nightcap and a long white dressing-gown.

“Valentine,” said the water-miller in a voice deep as the bottom of a well, “where have you been?”

“I’ve been to the windmill to see Cecily,” said Valentine truthfully and bravely.

“Sirrah!” cried the water-miller, shaking with such temper that his flowered nightcap trembled on his head. “Did I not forbid you to go to the windmill, on pain of being turned away from this my house? Go!” And the angry water-miller pointed a level finger out into the night.

“But, father,” protested Valentine.

“But me no buts,” thundered the miller. “Go, sirrah, for this house is yours no more.”

“But whither, father?” asked bewildered Valentine.

“That, sirrah, is your affair,” replied the angry miller. “Go anywhere you please; go find the Husbandman of the Hills!”

And with this last bit of advice, the wrathful water-miller pushed his son out of the mill and drew the long, grinding bolt across the door. A moment later the single light went out, and the mill was dark.

And now Valentine, in search of shelter for the night, sought out a farm in the gloom of the wooded hills. Leaving the broad white road, he followed first a country lane, then a pathway winding through a great woodsy mire, and then another lane, softly carpeted with moss and last year’s fallen leaves.

A star fell from the twinkling heavens; a hunting owl hooted in a tree. Ever so far away a silver bell struck the midnight hour.

Suddenly Valentine knew that he had followed a strange path, and was lost in the heart of the hills. It was a very strange path indeed, for the trees and the brambles along it seemed to have grown together in the dark, and pressed forward to form a thick imprisoning wall.

Uneasy at heart, the youth now turned to retrace his steps, only to see that the same mysterious trees had risen up behind!

Hours passed. Stars that were high in the heavens vanished over treetops in the east, a silvery dawn began to pale, and there were chirps and stirs and peeps and feathery noises in the wood. At the rising of the sun, Valentine arrived at the farm of the Husbandman of the Hills.

Now the Husbandman of the Hills—I must tell you—was the farmer of the fairies. It was from this farm in the hills that the goblins of the mountain-tops, the elves of the silver river, and the peoples of the fairy kingdoms of the world had their apples and clotted cream, their cherries and plums, and their butter-pats stamped with a crown.

The fairy farm lay in a green vale, magically walled about with briery trees. Only at the midnight minute could the wall be passed, and Valentine had chanced to cross it at the sixth stroke of the bell.

And now Valentine found himself made welcome by the Husbandman and his lady, the Goodwife of the Hills. The Husbandman was old; his face was ruddy and his hair silvery white, and in a smock of blue with a white collar was he clad. His spouse was elderly too, and wore a gown of green with short old-fashioned sleeves, a white housekeeper’s-apron, and a cap with ribbons and frills.

I wish I had time to tell you of how the long summer passed at the farm of the fairies—of the brewing, the baking, and the churning; and of how the green elves came to cut the grain with silver scythes no longer than your arm; of how a very young giant, who had a pleasant smile and was as tall as a tree, came to pitch the hay into the barn; of how the orchard goblins came to gather the wonderful apples into baskets of silver and gold; and of the enchanted bear who wore yellow spectacles and turned the butter churn.

Presently the leaves, though green, began to rustle dryly on the trees, and Valentine began to long for his own again.

“You have been a faithful laborer,” said the old Husbandman of the Hills. “A reward is yours. What shall it be?”

“But I seek no reward,” said Valentine, “for you gave me shelter, when shelter I had none.”

“A brave answer,” said the old Husbandman with a smile. “But you have earned your wage, good friend. I’ll give you a wish. Be in no haste to use it. And guard it well!”

And now Valentine turned from the vale, passed the magic bound at midnight, and found himself once more in an old, familiar pathway of the wood.

The autumn had been a rainless one, and the water-miller was having forty fits.

The mill brook was running dry!

Already there was scarce water enough to stir the heavy wheel. Another week without rain, and the bed of the brook would be naught but a length of puddles and pools. And the fine golden grain he had purchased was being threshed and winnowed, and would soon be arriving at the mill!

In and out of the door of the mill, a hundred times a day went the water-miller, now to stare at the vanishing brook, now to sweep the sky in hope of rain. But the dry leaves only rustled more dryly, and the sun was bright.

Worse yet, the Princess Celestia’s wedding day was fast approaching, and the Queen would soon be calling for her flour. And sure enough, the Queen’s herald presently rode again through the land, summoning all good millers to bring of their new flour to the palace before sundown on the seventh day.

The following week was indeed an anxious one for the miller by the brook. Alas for his fortunes—not a single drop of rain fell either in the meadows or the hills, and the brook ran dry. You might as well have tried to turn the wheel with a pitcher of water as to turn it with the trickle which remained.

On the night of the sixth day, the water-miller, humbled in heart, rode over to the windmill to make his peace and ask a boon. He would ask the wind-miller to grind the wonderful golden grain, and offer him half of the grain as a reward.

Now the wind-miller had not forgotten the water-miller’s trickery; so he received his old crony with anything but a friendly air.

“Grind grain for you, sir?” said the wind-miller, standing with arms akimbo and feet apart, “yes, sir; but only on one condition, sir, and that is, sir, that you let me choose my half of the grain, sir.

“And hearken, sir, one thing more, sir. You must bring the grain to the windmill this very night, sir.”

Now it came to pass that, as the water-miller, hanging his head, went out into the night, Cecily saw him, and ran to ask him for news of Valentine. But the water-miller was himself troubled because of the absence of his son, and could give no new tidings to the maid.

Groaning many a regretful groan, the water-miller loaded his fine two-wheeled scarlet cart with sacks of golden grain, and carried it to the windmill door. It was a warm night. The water-miller unloaded the sacks, mopped his brow with a red bandanna handkerchief, and sighed.

What a fool he had been not to play fair! What a fool to send away his son!

When the water-miller had driven away, the triumphant wind-miller took a great iron lantern, and went down to see the grain. For a moment or two he stood motionless, chuckling at his unexpected victory. Presently he called to Cecily to gather all the lights and candles she could find, and place them round about.

And now, toiling in a great blaze of candlelight, the wind-miller slowly and carefully sifted out for himself the better half of the wonderful grain. The remaining half—which was good enough, but full of husks and dust—he set apart for his rival.

The dawn was breaking as he finished the task. Some of the candles were burned out, and the lanterns were smoke-begrimed and dim. Wearily rubbing the grain-dust from his eyes, the wind-miller trudged up the circular stair and tumbled into bed. He would grind the grain into flour as soon as he woke in the morn.

And on that same still, autumn dawn young Valentine came out of the fairy wood.

When the wind-miller woke, he woke with a start, for he had slept late, and the sun was high. How warm and misty-moisty it was! Good heavens—there wasn’t a breath of wind!

A ship drifted becalmed upon the glassy sea; a blue haze of wavy summer heat lay upon the meadows, and over the wooded hills hung a motionless mass of bluish cloud with a rim of silvery white. There was not even air enough to stir a dead leaf hanging by a thread.

In and out of the door of the mill, like one distracted ran the miller; he stood upon the balcony and stared about at the sky, the greeny-leaden sea, and the helpless ship; he lifted a moistened finger to the air.

Oh, for a wind!

And now a ship’s bell in the mill struck the eight strokes of high noon, and presently the water-miller came hurrying to the mill in his scarlet cart. A moment’s glance at the two halves of golden grain told him of the wind-miller’s counterstroke, and he ran upstairs into the mill room full of wrath.

He lifted a moistened finger to the air. Good heavens—there wasn’t a breath of wind!

“I brought you my grain to grind,” he shouted at the wind-miller, “and you have not done so. I shall take it all back again, do you hear?”

“Wait; you made a bargain with me,” answered the wind-miller.

“I tell you I am done with the bargain,” cried out the water-miller in a passion.

“I tell you a bargain’s a bargain,” shouted the wind-miller. “Touch yon grain if you dare!”

And now, I am sure, the old friends and cronies would have come to blows, had not Valentine and Cecily suddenly hurried and rushed between them.

“Good sirs,” said honest Valentine, “pray you stand apart and do each other no wrong. The brook is dry; the wind is gone; of what use then is this disputed grain? Were it not best, mayhap, to begin anew?”

“Dear father,” said pretty Cecily, “Will you give your share of the grain to me?”

“With all my heart,” said the wind-miller, who hated brawling.

“And will you give your share to me, father?” asked Valentine.

“Yes, and gladly,” said the water-miller.

“Heart’s thanks to you both, good sirs,” said the youth with a bow and the maid with a courtesy. “And now,” continued Valentine, “you shall all behold a great wonder.

“O Husbandman of the Hills, you gave me a wish for a wage. Grant it to me now! I wish for a fine windmill-wind to blow till sundown of this day.”

Out of the hills came the wind. It swept up an inland dust, it sent the leaves on the higher crests a-flying, it rushed over the hot sea-scented meadows, it surged about the mill—and the great arms gathered it, creaked, groaned, and began a-spinning.

Valentine poured a shower of grain down an oaken slide into the grinding thunder of the heavy stones. The grain fell between the upper and the nether wheel, and presently the finest of new flour was pouring down below. And this new flour the three millers shook and sifted and cleansed until it was worthy of the Queen’s own hands, the golden batter-bowl, and the Princess Celestia’s cake. So wonderful indeed was the flour, that it instantly gained the rich reward the Queen had offered as a prize, and won for Valentine the appointment of miller to the King.

Touched by the happiness of their children, I am glad to say, the two millers agreed to forget their strife. And they shook hands, and became cronies again.

On the day following the wedding of the Princess Celestia, Valentine and Cecily were married. The little Princess sent them two thick slices of her cake. It was as white as snow, and frosted with sugar, and there were candied plums, and cherries, and citron nibbles in each slice.

And Valentine and Cecily rejoiced, and lived happily together all their days.

Once upon a time, on a fine spring morning, a country lad named Hugh took his fish pole from a corner and went to try his luck in a brook beside the road. Now it fortuned that as he stood upon the grassy bank, casting about in the broad shallows of the stream, the boy heard the mighty sound of many men singing together, and presently he beheld a regiment of soldiers on the march. In uniforms of red-and-white they were clad, and an officer in red-and-white and gold was riding at their head.